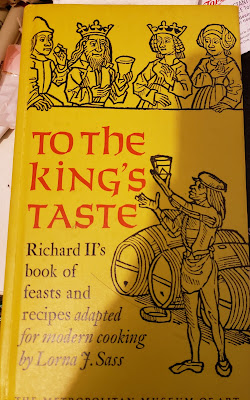

Scroll Blank - Fool with cusped loaf

Details of the original image:

Illuminated Manuscript, Carrow Psalter, Fool with bladder on stick eating cusped loaf, Walters Manuscript W.34, fol. 113rShelf mark: W.34

Manuscript: Carrow Psalter

Text title: Psalter-Hours

Abstract: This English manuscript was made in East Anglia in the mid-thirteenth century for a patron with special veneration for St. Olaf, whose life and martyrdom are prominently portrayed in the Beatus initial of Psalm 1. Known as the “Carrow Psalter” due to its later use by the nunnery of Carrow near Norwich, it is more accurately described as a psalter-hours, as it contains, among other texts, the Office of the Dead and the Hours of the Virgin. The manuscript is striking for its rich variety of illuminations, including full-page cycles of saints, martyrs, and biblical scenes, as well as historiated initials within the Psalter, and heraldry added in the fifteenth century to undecorated initials in the Hours of the Virgin. Especially notable is the miniature portraying the martyrdom of St. Thomas Becket, for after Henry VIII found him guilty of treason in 1538, his image was concealed by gluing a page over it rather than destroying it, and it has since been rediscovered.

Date: Mid-13th century CE

Origin: East Anglia, England

Form: Book

Genre: Devotional

Language:The primary language in this manuscript is Latin.

Support material: Parchment. Medium-weight cream-colored parchment; slightly heavier-weight parchment used for full-page miniatures

Dimensions: 17.6 cm wide by 24.7 cm high

Written surface: 12.0 cm wide by 17.4 cm high

Layout:

Columns: 1

Ruled lines: 14

Layout does not apply to calendar (written surface 12 x 19 cm, 32-33 ruled lines)

Contents:fols. 1r - 321v:

Title: Psalter-Hours

Hand note: Littera prescissa, with smaller size used as cues for psalms cited in liturgical texts, antiphons, versicles

Decoration note: Manuscript opens with cycle of ten full-page saints’ portraits/martyrdom images interspersed with their suffrages, followed by prefatory cycle of eleven mixed full-page and two-register illuminations depicting Adam and Eve and Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; second group of five full-page Christological illuminations follow that repeat scenes already depicted, and may have been added; images typically glued back-to-back with blank side of previous folio, and have highly burnished gold grounds, rectangular frames; Psalter contains eleven historiated initials at openings of select psalms and one within hours (six to seven lines high); eleven heraldic arms added in fifteenth century within unadorned initials, beginning with Psalm 119 and found throughout the hours; smaller initials in gold or blue with intricate blue and red pen flourishes begin each line of text (one to four lines high); rubrics in red; text in black ink. [1]

Technique:

This project was an attempt to reproduce this beautiful manuscript image which was chosen to be entered into the arts and sciences competition at Summer’s End 2023, which had the theme of “pie”. Anything pie related. More on that, later.I used gouache and ink on paper rather than vellum and period pigments as I still have not mastered those advanced materials. Working from a high resolution image of the manuscript, [2] I removed the background colors and printed out the image. The design was transferred to the paper by tracing over a light box.

I kept the colors similar, to the source, as I liked the reds and blues, although I used a lighter shade of red for the dragon making up the tail of the ‘Q’. I do like the combination of red and blue, particularly with the white lines. Several layers of gold paint were used to make the background and border stand out. The goal was to produce an image that would stand out and be visible when it was displayed in court. This was my first use of ox gall. I had had issues with getting even coats of the dark red and blue and it was suggested that I try adding a drop or two of ox gall to the water and gouache. I purchased a bottle of Holbein ox gall and a couple of drops did help immensely.

Once the all of the paint had dried, I outlined all of the sections with black ink to make the image stand out. For the white, I used Winsor and Newton white ink (#974) for the lines and Winsor and Newton Permanent White gouache for the solids. I had intended to have a fainter white for the scalloped shapes, but the white paint was picking up too much of the blue underneath and I was not able to control the consistency. In the end, I used a heavier layer of white to make a solid shape, and then painted blue circles in the white and surrounded the blue with red dots. Both in honor of the source image and because I like how the small amount of red does stand out next to the blue.

What does this have to do with pie?

My original intent was make some sort of verbal jigery-pokery to explain that what the figure was holding was a pie and not manna, as I had thought it was. I started working on the image before I paid attention to the title: I had thought that it was an image of Moses or another person eating manna while wandering in the desert looking for the promised land. I knew that the Pslter had inhabited initials of scenes from the Book of Exodus and had assumed that this image might have been from that book. I was planning on arguing that we don’t know what manna was. In fact the word manna is derived from the Hebrew question “Ma’n Hu?” or “What is it?” [3] Perhaps manna was actually Hostess fruit pies.Then, when I was gathering my notes for this documentation I noticed the title of the page: Fool with bladder on stick eating cusped loaf started the page of Psalm 51. Definitely not from Exodus. So, what does “cusped loaf” mean? I spent the better part of a day trying to track this down. Cusped has a few meanings in 13th century England. One is the precursor to “cupped”. As in cupped hands. So, it could refer to something that could be held in one hand. Cusped could also mean something that was enclosed, like a hot pocket or a Cornish pastry. Cusped could also mean something that was scalloped or had pointy bits, like an arch or like the loaf in the fool’s hand, in the image. The last result that I found was in relation to fools and jesters. A cusped loaf could refer to a enclosed pie filled with custard that was used as a weapon against another jester or against someone whom the jester’s boss found tiresome. A medieval version of the pie fights of the early cinema. Or, the jester or fool could have eaten it in a very messy fashion, either for comic relief or to lampoon someone sitting at feast. I was unable to discover anything more about such custard pies, such as what color the custard was, as their intent was to make a mess. The Scheide Psalter-Hours [4] has a similar fool holding a “bauble and loaf”, only wearing just a cloak. I don’t know why these two psalters chose to depict fools for Psalm 51 and 52: The first begins with “Have mercy on me, O God” and the second, “Why do you boast of evil, you mighty hero?” But, the purpose of this paper is to explain my illumination and it’s connection to pies. Further research into professional fools and the Psalms will have to wait until another research project.

References:

Anglo-Norman Dictionary :: Word of the Month: Nice! An Anglo-Norman Insult. https://anglo-norman.net/word-of-the-month-nice-an-anglo-norman-insult/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.Bennett, Adelaide. “The Scheide Psalter-Hours.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 55, no. 2, 1994, pp. 177–223. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26509121. Accessed 10 Sept. 2023.

“Bible Gateway Passage: New International Version.” Bible Gateway, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%2051&version=NIV. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

“Biblical Hebrew Words and Meaning.” Hebrewversity, 14 Mar. 2018, https://www.hebrewversity.com/word-mannamean-hebrew/.

Buhrer, Eliza. “But What Is to Be Said of a Fool?: Intellectual Disability in Medieval Thought and Culture” in Mental Health, Spirituality and Religion in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age (Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern Culture), Ed. Albrecht Classen (Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2014). www.academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/18029983/_But_what_is_to_be_said_of_a_fool_Intellectual_Disability_in_Medieval_Thought_and_Culture_in_Mental_Health_Spirituality_and_Religion_in_the_Middle_Ages_and_Early_Modern_Age_Fundamentals_of_Medieval_and_Early_Modern_Culture_ed_Albrecht_Classen_Berlin_and_Boston_Walter_de_Gruyter_2014_. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

“Cusped.” The Free Dictionary. The Free Dictionary, https://www.thefreedictionary.com/cusped. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Cusped - Advanced Search Results in Entries | Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/search/advanced/Entries?textTermText0=cusped&textTermOpt0=WordPhrase&dateOfUseFirstUse=false&page=1&sortOption=AZ&tl=true. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Cusped - WordReference.Com Dictionary of English. https://www.wordreference.com/definition/cusped. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Definition of CUSPED. 5 Sept. 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cusped.

Dienstbier, Jan. The Image of the Fool in Late Medieval Bohemia, in: Umění/Art LXIV, 2016, 354–370. www.academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/32931743/The_Image_of_the_Fool_in_Late_Medieval_Bohemia_in_Um%C4%9Bn%C3%AD_Art_LXIV_2016_354_370. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Ewbank, Anne. “How Pie-Throwing Became a Comedy Standard.” Atlas Obscura, 10 July 2018, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/why-do-people-throw-pies.

Flickr Photostream for Walters Art Museum Carrow Psalter, Fool with bladder on stick eating cusped loaf, Walters Manuscript W.34, fol. 113r. https://www.flickr.com/photos/medmss/6165863401/in/photolist-btQupQ-aoREnF

Fool | Etymology, Origin and Meaning of Fool by Etymonline. https://www.etymonline.com/word/fool. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Model, Ben. “Pie-Eyed – In Search Of The Pie Fight’s Origins.” Ben Model, 18 Jan. 2020, https://silentfilmmusic.com/charlie-chaplin-pie-fight/.

Okyere, Kojo. The Ways of the Fool A Literary Reading of Psalm 14.Pdf. www.academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/29319309/The_Ways_of_the_Fool_A_Literary_Reading_of_Psalm_14_pdf. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Oliver, Judith. “The Mosan Origins of Johannes von Valke.” Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, vol. 40, 1978, pp. 23–37. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24657566. Accessed 10 Sept. 2023.

“Pain Quotidien: Images of Bakers in Medieval France.” Different Visions, https://differentvisions.org/images-of-bakers/. Accessed 9 Sept. 2023.

Pantry, The Past is a Foreign. “Chastletes: 1390.” The Past Is a Foreign Pantry, 7 Aug. 2020, https://thepastisaforeignpantry.com/2020/08/07/chastletes-1390/.

Sforza Tarabochia, Alvise. “The Staff of Madness: The Visualization of Insanity and the Othering of the Insane.” History of Psychiatry, vol. 32, no. 2, June 2021, pp. 176–94. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0957154X21989224.

Sidsel. “Small Medieval Meat Pies - Hand Pies - Postej & Stew.” Postej & Stews, 14 May 2017, https://postej-stew.dk/2017/05/small-meat-pies/.

Walters Art Museum: Digitized Walters Manuscripts: Walters Ms. W.34, Carrow Psalter. https://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W34/description.html

[1] https://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W34/description.html

[2] Provided by The Walters Art Museum’s Flikr page.

[3] Hebrewversity

[4] Scheide Library ms 16, folio 42V, Psalm 52